Smile if you’re not wearing knickers.

Mud. I hate walking on it but love handling it. Followers of this blog will know that I have had encounters and slippages with the substance in the past. Nowadays I am much more prudent when while on it, and have even developed a technique for walking downhill on mud which is half penguinesque and half Chaplinesque. Bradlow Knoll was very muddy.

Apologies for the attention-grabbing title. It is only barely relevant to the subject of mud, which is what I want to talk about, but it will nevertheless justify itself at a later stage.

Ceramicists make mud look good, I was thinking to myself, and what is the difference between mud and clay anyway? I was driving along a wet, muddy and slimy track in search of a tarmacked road and civilization. The Satnav was telling me it was the best route, but satnavs are not to be trusted. The sun was setting and it was drizzling. The car was beginning to slide on the gradients and long bends – there was nobody to be seen, only the pale chalky mud of what turned out to be The Ridgeway, ancient Britain’s equivalent of the M4 motorway, which was what I was actually looking for before getting into this mess.

The track’s surface varies from chalk-rutted farm paths and green lanes (which become extremely muddy and pot-holed after rain) to small sections of drivable roads covered in gravel and crushed stone. It is the oldest trackway in UK. It is 87 miles long. For at least 5,000 years travellers have used it as a reliable trading route from the Dorset to the Norfolk coast.The high dry ground made travel easy and provided a measure of protection by giving traders a commanding view, warning against potential attacks. I, on the other hand, was only trying to get to London to visit an exhibition or two before the satnav led me into this quagmire.

Despite wondering if I was breaking the law, I had just previously enjoyed driving past the White Horse of Uffington up on its hill. This is prehistoric landscape – silt deposits show the figure was made in the period between 1380 BC and 550 BC, confirming it as Britain’s oldest chalk figure – and still conveys a timeless quality with its sloping open contours and scattered dwellings.

Before getting back to mud vs clay, I can confirm that the track is a designated bridleway (shared with horses and bicycles), but also includes parts designated as byway, which permits the use of motorised vehicles – though not between October and April, which is when I was on it. Never trust Satnavs. I did get to London.

As you probably all know by now, clay is a specific type of mud, defined by its fine particle size and mineral composition, giving it a stickiness and ability to hold shape, while mud is really soil mixed with water, but can also be used in pottery. If you dig up some mud and manage to roll it into a tubular shape and then coil it without cracking, that’s mud good enough for pottery – though ideally you would add sand and other particles to strengthen it when firing.

Once in London, at the National Gallery, I came across Richard Long’s Mud Sun. This is made entirely of mud from the River Avon applied by hand onto a black background. The hand marks highlight the physical process of making art, and it works as a flat sculpture and at the same time reveals how it was made. It’s a very direct form of human creativity, and took me back to the ancient Ridgeway, though I’m not claiming that the marks left on the car show any creativity.

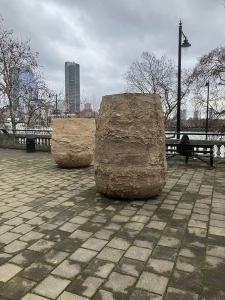

One of the exhibitions was held on the roof of the entrance to Temple Station by the Thames. Jodie Carey’s Earthen are two enormous vessels made entirely outdoors on a hilltop using the earth of East Sussex, each piece cast in the ground and then wrapped in hand-stitched cloth and buried. Bits of soil, stone and plant roots are all part of the shaping process. It draws on the symbol of the simple pot used across the world and across time – but these are towering and imposing. If you click on the blue link above, it will take you to a very good video that explains the process.

The (non-mud) exhibition at Tate Britain was dedicated to John Constable and J M W Turner. They are different from each other; Constable very earthbound, a great observer of land, trees and people at work, and probably better at mud that Turner, whereas Turner tries to capture air and light, so that some of his paintings are almost abstract. His painting of the gardens at Petworth would float away were it not for the deer in the foreground pinning it down like an anchor. He is a tonalist painter, using muted colours, often a limited palette, and often wet-on-wet or glazed layers to achieve a harmonious and unified scene. He is fabulous.

At PCA we tend to go the other way and paint the pieces with contrasting tones – red with green, white and blue or brown, black dots on a lighter background, etc – not that we claim the same stature as Mr Turner; we are quite modest (more confident marketing required here, please – Spiro). We are going through a “spot” phase right now, as you can tell from the images scattered around this blog.

The reason for this blog’s title is to lure you into reading a short story published online by Literally Stories. It’s only 990 words long, so won’t take up your time. Like a vase that isn’t filled with flowers, or a painting that’s never seen, or a sonata that’s never heard, my story will not exist unless somebody reads it. As the poet Samuel Menashe says:

A pot poured out

Fulfills its spout

You can read “Smile if you’re not wearing knickers” by clicking here.

Mud facts: playing in mud makes you happier. Pigs wallow in mud to keep cool because they do not have sweat glands. Mud packs owe their popularity to vitamin E in mud which revitalises the skin. The band Mud had 14 UK Top 20 hits between 1973 and 1976, including three number ones. Other English words for mud include clabber, clauber, clart, cloom, glaur, groot, grummel, lutulence, slather, sleck, slike, slutch, sposh, stabble.

Bad mud joke:

Paul and Vince were digging a ditch when Paul made a careless swipe with his spade and cut off the Vince’s ear.

“Help me find it in all this mud,” cried Vince. “Then they can sew it back on.”

After a couple of minutes, Paul shouted, “Here it is”, and handed Vince the ear.

“That’s not it,” said Vince, and threw it back in the muddy ditch. “Mine had a pencil behind it.”