Fiat Lux

As the nights draw in and the days get shorter with the coming of Autumn and Winter (at least here in the Northern Hemisphere) belatrova‘s thoughts turn to light and dark, and to the importance of that everyday object, the lightbulb. Where would we be without it?

Imagine the belatrova team groping around in the workshop carrying tallow candles or rushlights – an Elfin Safety issue, surely.

Rushlights? Well, rushlights were the medieval poor person’s lightbulb, made by repeatedly coating a rush in hot fat, building up the layers to create a thin candle.

The rushes were peeled and then hung up in bunches to dry. Fat was melted in boat-shaped grease-pans that stood on their three short legs in the hot ashes in front of the fire – belatrova’s tripods look a little like them. The bunches, each of about a dozen peeled rushes, were pulled through the grease and then put aside to dry.

Tallow candles do not sound so good either – a sooty wick burning in animal fat, usually from cows or sheep, though pig’s fat was the worst – given to letting off a great stink when burning.

buying your tallow in the 14CAnyway, along came the oil lamp, with all the smell and smoke and sooty walls that must have created. Then the oil lamp was superseded by gas, which must have improved people’s ability to read or write and do so many other things, though it did have its drawbacks: explosions and lack of oxygen in the air – the latter a reason for Victorian ladies fainting, other than for their tight corsets, in their gas-lit drawing rooms.

Today our gas is natural, piped from beneath the sea. It burns much more brightly than the baked coal gas used between late Georgian times and the 1970s.

Electricity on the other hand opened up new opportunities.

Thanks to Michael Faraday‘s principle of electromagnetic induction in 1831, generators could start to produce electricity in large quantities at a modest cost. This meant that scientists were able to experiment with electricity and lighting.

The first electric lights were Arc Lamps. The principle is that two pieces of carbon, connected to an electricity supply, are touched together and then pulled apart. A spark or ‘arc’ is drawn across the gap and a white hot heat is produced.

And so to the lightbulb

While most modern light bulbs barely last a year, the Centennial Light is still shining on after an incredible 110 years. It is the world’s longest-lasting lightbulb. It is at 4550 East Avenue, Livermore, California, and maintained by the Livermore-Pleasanton Fire Department. Is this evidence for the existence of planned obsolescence in modern lightbulbs?

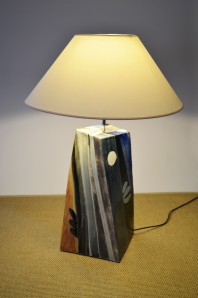

You may be asking yourself why belatrova is rambling on about lighting. Well, we too are doing our bit in the fight against encroaching darkness. We just want to show you our first ceramic table and floor lamps.

What do you think? We like the twist in the ceramic base – it takes two to of us to make, but we think it is worth the effort.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!